A few interesting things about health we read this week.

Ultra-processed foods are making people sick and reducing their lifespans.

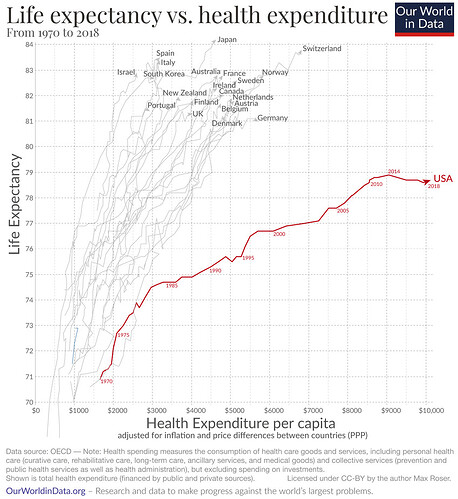

You might have seen this shocking chart on social media showing the life expectancy of Americans compared to healthcare spending.

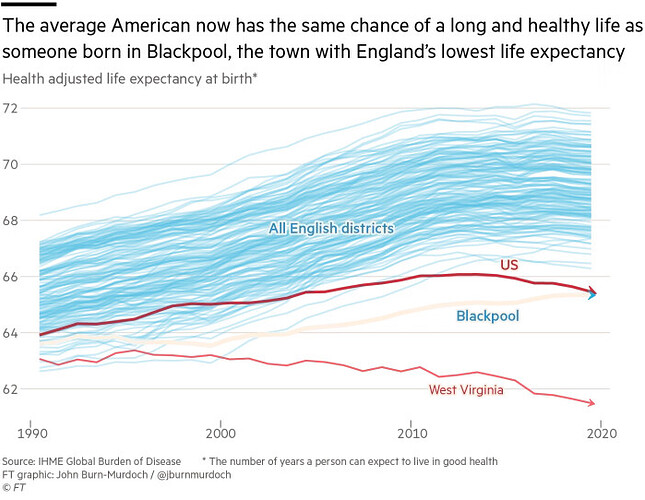

Or this one showing that average American lifespan is the same as someone from Blackpool, the UK city with the worst life expectancy.

What’s happening?

One reason is that we are eating ourselves sick. There have been a lot of articles in the last few months, and there’s now a book on the topic.

Christoffer van Tulleken is an infectious diseases doctor at the National Health Service (NHS), University College London Hospitals (UCLH). He’s also a broadcaster on a kids’ science show for the BBC, a podcaster, and an author. He has a new book called Ultra-Processed People. I haven’t read the book yet, but the reviews have been showing up everywhere. The book is about ultra-processed foods and how they’re getting us addicted first and killing us later. To write the book, the good doctor became a guinea pig himself by substituting 80% of this diet with ultra-processed foods like soda, chips, and fast food for a month.

The effect of processed foods, in the words of the doctor, is alarming. They make us crave more, lead to obesity and other health issues.

Two disturbing excerpts from a podcast appearance of his on NPR:

He found that people eating ultra-processed food eat around 500 calories more per day, even when you compare them to control subjects eating the same amount of fat, salt, sugar and fiber, but on a whole food diet. So it is the ultra-processed food that interferes with our body’s ability to say, you know what? I’m done. I can stop eating now.

The simplest thing is to do what Chile are doing. You put a big black hexagon on ultra-processed food. And you don’t ban it. You don’t tax it. You can’t tax this food because it’s the only available and affordable food for many, many people in the U.S. and the U.K. But you can start to warn people that it has negative health outcomes strongly associated with it.

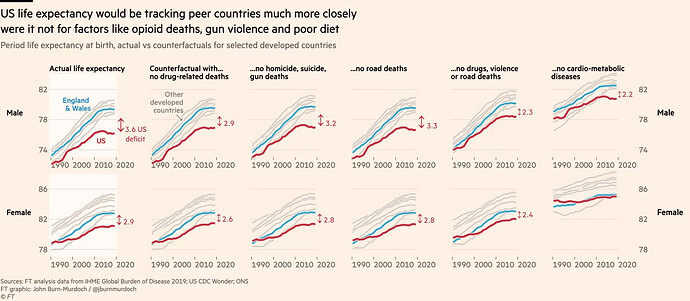

Critiques about processed foods can also sound like rants, but there’s mounting evidence. This chart is from a piece in the Financial Times last year. It shows the counterfactual life expectancy in the absence of common causes of death and health issues like drugs, gun violence, and road accidents.

The latest treatment of the book comes from Adam Gopnik in The New Yorker. It’s not a review so much as adding historical context to debates about processed foods and the difficulty in figuring out the good processed vs the bad processed. Nonetheless, despite some mild skepticism about the tone of the book and the framing of debates, even Mr. Gopnik agrees about the dangers of ultra-processed foods. It’s a long read, but if you don’t have the time read, here’s an annotated version with the highlights.

The grim tale eventually takes van Tulleken on a long flight to backcountry Brazil, where he discovers that the Nestlé Corporation has brought its snacks, by boat, to Indigenous peoples, with the predictable effect of making Amazonian kids prefer junk food to the ancient and healthy staples of roots and berries. “I have not found any evidence that there were children with diet-related diabetes in these parts of Brazil until enterprises like the Nestlé boat,” he writes. We are being purposefully addicted, and on a planetary scale, he concludes. Ultra-processed foodstuffs will alter our children’s brains and enslave them to a global capitalist economy.

A few months ago, researchers from the University of Michigan and Virginia Tech published a study concluding that processed foods are as addictive as tobacco.

The research, published in the current issue of Addiction, offers evidence that highly processed foods meet the same criteria used to identify cigarettes as an addictive substance:

- They trigger compulsive use where people are unable to quit or cut down (even in the face of life-threatening diseases like diabetes and heart disease)

- They can change the way we feel and cause changes in the brain that are of a similar magnitude as the nicotine in tobacco products

- They are highly reinforcing

- They trigger intense urges and cravings

Dive deeper

America has the lowest lifespan but the highest per capita spending on healthcare. To say that the American healthcare system is broken would be an understatement.

A study looking at the life expectancy across income ranges in India.

Life expectancy at birth was 65.1 years for the poorest fifth of households in India as compared with 72.7 years for the richest fifth of households. This constituted an absolute gap of 7.6 years and a relative gap of 11.7 %. Women had both higher life expectancy at birth and narrower wealth-related disparities in life expectancy than men. Life expectancy at birth was higher across the wealth distribution in urban households as compared with rural households with inequalities in life expectancy widest for men living in urban areas and narrowest for women living in urban areas.

Research

One of the common pieces of fitness advice you hear is that training to failure is the only way to induce muscle growth. Is it?

A meta analysis of 15 studies by Grgic et al. (2022) concludes that, training to failure isn’t a necessary condition for muscle growth.

Training to muscle failure does not seem to be required for gains in strength and muscle size. However, training in this manner does not seem to have detrimental effects on these adaptations.

Note: Meta studies are analyses of existing studies.

The topic of flours came up recently in the internal Rainmatter group, and I learned that there’s a significant loss of nutrients in grains during the milling process. As obvious as it might sound, I was blissfully unaware of this. I started googling and came across this Harvard public health series on nutrition. It’s a good explainer for normal people like me who don’t use terms like “nutrient profile” and “micronutrients”.

Cautionary tale

Speaking of nutrition, I read this wild piece about Daily Harvest, a buzzy health food startup that’s raised its last round at $1.1 billion. One of its plant protein products landed over 130 people in the hospital with serious health complications. Now the company is facing multiple lawsuits. It’s a cautionary tale that highlights multiple things:

- Influencers peddling the latest avocado pineapple baobab fruit bittergourd peanut lettuce smoothie are not experts on health.

- The need for regulations and regulatory guidelines for “wellness” products and “superfoods”.

- More importantly, regulatory guidelines around advertisements of health products. It’s amazing that health companies can get away with saying ridiculous things. Reminds of Gwyneth Paltrow’s Goop and her $100 crystals.

Research peddlers

Speaking of research, this week I read this piece about publishing fraud in a lab headed by a superstar neuroscientist and the president of Stanford University. On the one hand, it’s amazing that we live in a time when so much research is easily accessible. But on the other hand, the incentives for research are broken. Researchers are incentivized to prioritize quantity over quality. Then there’s the issue of prestige, getting published in prestigious journals like Science and Nature carries massive rewards, and some researchers commit fraud to get published.

A 2016 study by a handful of prominent research misconduct investigators — including the well-known image analyst and microbiologist Elisabeth Bik, who helped identify a number of the manipulations in the work coming out of Dr. Tessier-Lavigne’s labs — showed that around 3.8 percent of published studies include “problematic figures,” with at least half of those showing signs of “deliberate manipulation.” But only approximately 0.04 percent of published studies are retracted. That gap, which shows a lack of accountability among individual researchers and the scientific journals, is a profoundly unfortunate sign of a culture in which admitting failures has been stigmatized, rather than encouraged.

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/30/opinion/stanford-president-student-journalist.html

I’m really interested in behavioral science, and I follow the latest developments and research closely.

In the last decade, there’s been a growing replication crisis in the field 1,2,3. In an ironic twist of fate, just about a month ago, a famous Harvard professor who studies dishonesty and has written books on the topic got caught for fudging data in her research papers. But a cursory look suggests, the replication crisis is equally widespread in the hard sciences as well.

I don’t know if this is a limited observation or if my observation is even valid. But In the past decade, an interesting development I’ve observed on social media is that more people seem to be consuming academic research. I still get surprised when people readily share PubMed and SSRN links. On the whole, I think this is a good thing. But I am not sure if people appreciate the level of fraud in scientific studies or question just how unreplicable most studies are. The other trend is that a lot of mainstream publications now publish accessible summaries of studies, and the number of people saying I read thus study and it says… or but this study shows has shot up.

You can find a research paper that confirms any opinion you have. So being skeptical by default about academic research is a good thing. At the very least, looking at multiple studies on the same topic is a good start. How do you spot sham research? There are no easy answers, and it takes some work. I recently heard a good podcast on the same topic. You can listen from the 20 minute mark onward, but the discussion on spotting fraud starts around 26 minutes in.